Source Control Standards

As teams grow, implementing certain standards becomes mandatory. Otherwise, managing projects or source code and maintaining the efficiency of the working environment becomes difficult.

Now that we've given a general answer to questions like "why are we doing this?" or "isn't this a waste of time among all the work?" for the standards we're about to discuss, let's take a look at what we'll cover in this document;

- Semantic Versioning

- Perfect Commit;

- Perfect Commit Messages

- Conventional Commits

- Branch Naming

Semantic Versioning (SemVer)

If you're wondering why there's a section about versioning in a document called Source Control Standards, be patient and keep reading 😉

What is Semantic Versioning?

Semantic versioning is a standard way to determine version numbers in software projects. This standard ensures that version numbers are meaningful and predictable. Semantic versioning is typically used in the MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH format.

Let's take a look at what each section means and when it should be incremented:

- MAJOR: Incremented when backward-incompatible changes are made.

- MINOR: Incremented when backward-compatible new features are added.

- PATCH: Incremented when backward-compatible bug fixes are made.

Why Should You Use Semantic Versioning?

- Understandability: You can easily understand how much the software has changed and what kind of effects these changes have on compatibility from the version number.

- Reliability: Users of the software can better assess the risks of updates by looking at the version number.

- Collaboration: When team members and users know the meaning of version numbers, they feel more confident about contributing to the project and using the software.

How to Do Semantic Versioning?

Let's assume we're developing an API for an e-commerce site as a team. Below are scenarios and how the version number would change in these scenarios:

- You're adding basic features to the API and it's not yet suitable for users, meaning you don't have a stable version. In this case, the first version number should be

0.1.0. - You added the endpoints necessary for users to log in. In this case, the next version number should be

0.2.0. - You noticed there were bugs in the newly added endpoints and released a version fixing them. In this case, the version number should be

0.2.1. - You completed the basic features of the API and it's now ready for users. In this case, your first version number should be

1.0.0.- Releasing a stable version also means delivering the final trial version. So version numbers

0.2.1and1.0.0can actually be the same. In this case, backward incompatibility is not expected. Backward incompatibilities usually appear in versions after1.0.0.

- Releasing a stable version also means delivering the final trial version. So version numbers

- You added certain features to your API and the current version number is

1.17.4. To improve API performance and fix security vulnerabilities, you updated the framework and packages you use, and consequently made backward-incompatible changes to the API. In this case, your next version number should be2.0.0. - Your business unit asked you to add a new payment infrastructure. In this case, your new version number should be

2.1.0

Now that we've semantically versioned our imaginary e-commerce site, CONCLUSION;

Semantic versioning is a standard for keeping your project organized and understandable. At every stage of the project, we can provide clearer information about the project's status to users and team members by correctly updating version numbers. Using this standard, we can make the software development process more manageable and reliable.

For rules you should follow when applying Semantic Versioning and more information, you can check out the SemVer Official Website.

Perfect Commit Messages

Although they may seem unimportant, commit messages are an important part of the software development process. A well-written commit message helps both you and your team members understand the project better. It eliminates questions like "Who made this change and why?" and provides significant time savings, especially for team members who constantly work on different projects.

Writing the perfect commit message is only half the job; breaking changes into parts and planning what should be added to these parts is equally important. Commits can play an important role in how you approach a task. Logically grouping changes into commits also allows you to improve the software development process by planning a task and breaking it into smaller pieces.

This will make you think more about the task and the solution you're producing, not just at the beginning but also when breaking changes into commits and writing the commit message. This can help you review your implementation and perhaps notice overlooked edge cases, missing tests, or anything else you might have forgotten.

How?

Now that we've left the task of properly breaking our development into commits to you, let's answer the question of how we should write the commit message. Consistency is very important here, so teams should first discuss and agree on the following three topics;

- Style: Plays an important role in making the commit history readable. Includes topics such as grammar, punctuation, capitalization, and line lengths.

- Content: Standardizing content is not easy. However, it should include information about why the changes were made and how they were implemented, and when necessary, the technical details and effects of the changes.

- Metadata: Should include additional information such as Issue Tracking IDs, notes indicating whether changes have been tested, or findings or comments obtained during the code review process if necessary.

There's no single way to address these three topics, so it's open to discussion, but most Git commit messages follow a certain pattern. We'll examine this commonly used pattern below.

Template

[subject]

[optional body]

[optional footer(s)]

Subject

Just like in an email, the subject is a very important part. It's usually the first, perhaps the only part people will read, so it should be visually appealing and easy to understand, avoiding unnecessary capitalization and punctuation, and using the right keywords.

The imperative mood is standard; when Git creates a commit on your behalf (for example, when you run git merge or git revert), it uses the imperative mood. This means you should write "Add" instead of "Added" or "Adds". The text in the subject should complete this sentence: "If applied, this commit...". Most teams apply the following rules for commit subjects;

- Should start with a capital letter

- Should not end with a period

- Should be 50 characters or less

Example of a good commit subject: Update configuration files with new staging URL

Again, these rules are not strict rules like "you can't do this, you'll turn to stone if you do". You can even add emojis to your commit messages if you want 😊

Body

The subject is often self-explanatory, but sometimes it's necessary to add more information to the "body" field. We use this field to provide more context about WHAT and WHY changed.

Most teams apply the following rules for commit body;

- Use a blank line to separate from the subject

- Organize paragraphs with blank lines or bullet lists etc.

- Line length should be 72 characters or less

Tim Pope's example can be shown as an example of the goal we should aim for in terms of style:

Short(50 chars or less) summary of changes

More detailed explanatory text, if necessary. Wrap it to 72 characters.

The blank line separating the summary from the body is critical (unless

you omit the body entirely); tools like rebase can get confused if you run

the two together.

Further paragraphs come after blank lines. Bullet points are okay, too.

- Use a hyphen or asterisk for bullet points.

- Capitalize the first letter of each point.

Metadata/Footer

We can add Azure DevOps tasks or user stories, Pull Requests, or Jira tickets related to the commit to the footer. This field is also where deprecated features and backward-incompatible changes should be indicated. Example;

BREAKING CHANGE: <summary>

<blank line>

Fixes #<user story>

Closes #<pr>

When we put it all together, our commits should look like the example below;

Add user authentication feature

- Implemented user authentication using JWT tokens for secure login.

- Added user registration functionality with password hashing for security.

Fixes #123

Closes #456

Not Tested

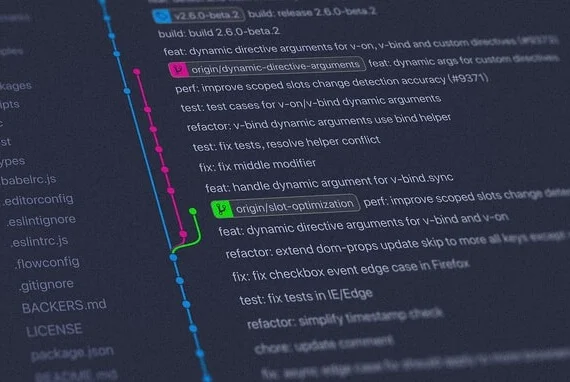

Conventional Commits

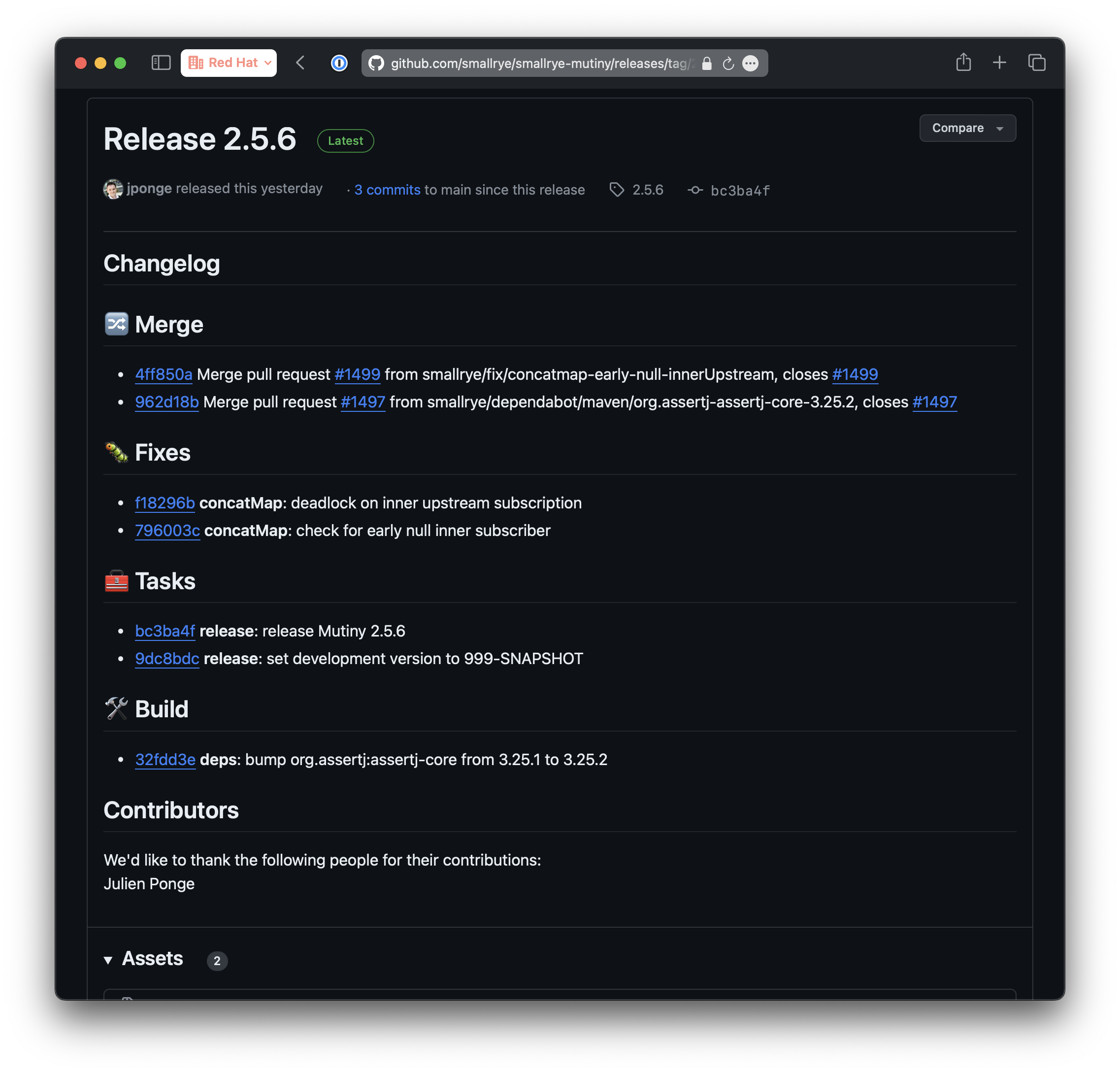

On top of the perfect commit we created in the previous section, we're trying to create a roof over the commit message by applying the standards set in the Conventional Commit specification, so we can get a meaningful commit history, obtain various reports from this history, and gain certain capabilities. In other words, we'll make our human-readable commit messages human & machine-readable. Also, this specification is compatible with Semantic Versioning.

Template

<type>[optional scope]: <subject>

[optional body]

[optional footer(s)]

A Conventional Commit must contain the following structural elements;

- fix: A commit of type

fixfixes a bug in your code (parallel toPATCHin semantic versioning). - feat: A commit of type

featadds a new feature to your code (parallel toMINORin semantic versioning). - BREAKING CHANGE: A commit with a footer starting with

BREAKING CHANGE:or with a!added after type/scope introduces a backward-incompatible change (parallel toMAJORin semantic versioning).

Other commonly used types:

- docs: Documentation only changes

- style: Changes that don't affect the meaning of the code

- refactor: Code change that neither fixes a bug nor adds a feature

- perf: Performance improvements

- test: Adding missing tests or correcting existing tests

- build: Changes that affect the build system or external dependencies

- ci: Changes to CI configuration files and scripts

- chore: Other changes that don't modify src or test files

- revert: Reverts a previous commit

Examples

A commit message with subject and breaking change footer:

feat: allow provided config object to extend other configs

BREAKING CHANGE: `extends` key in config file is now used for extending other config files

A commit message with ! to draw attention to breaking change:

feat!: send an email to the customer when a product is shipped

A commit message with scope:

feat(api)!: send an email to the customer when a product is shipped

A commit message without body:

docs: correct spelling of CHANGELOG

For remaining details, check out the Conventional Commits Specification.

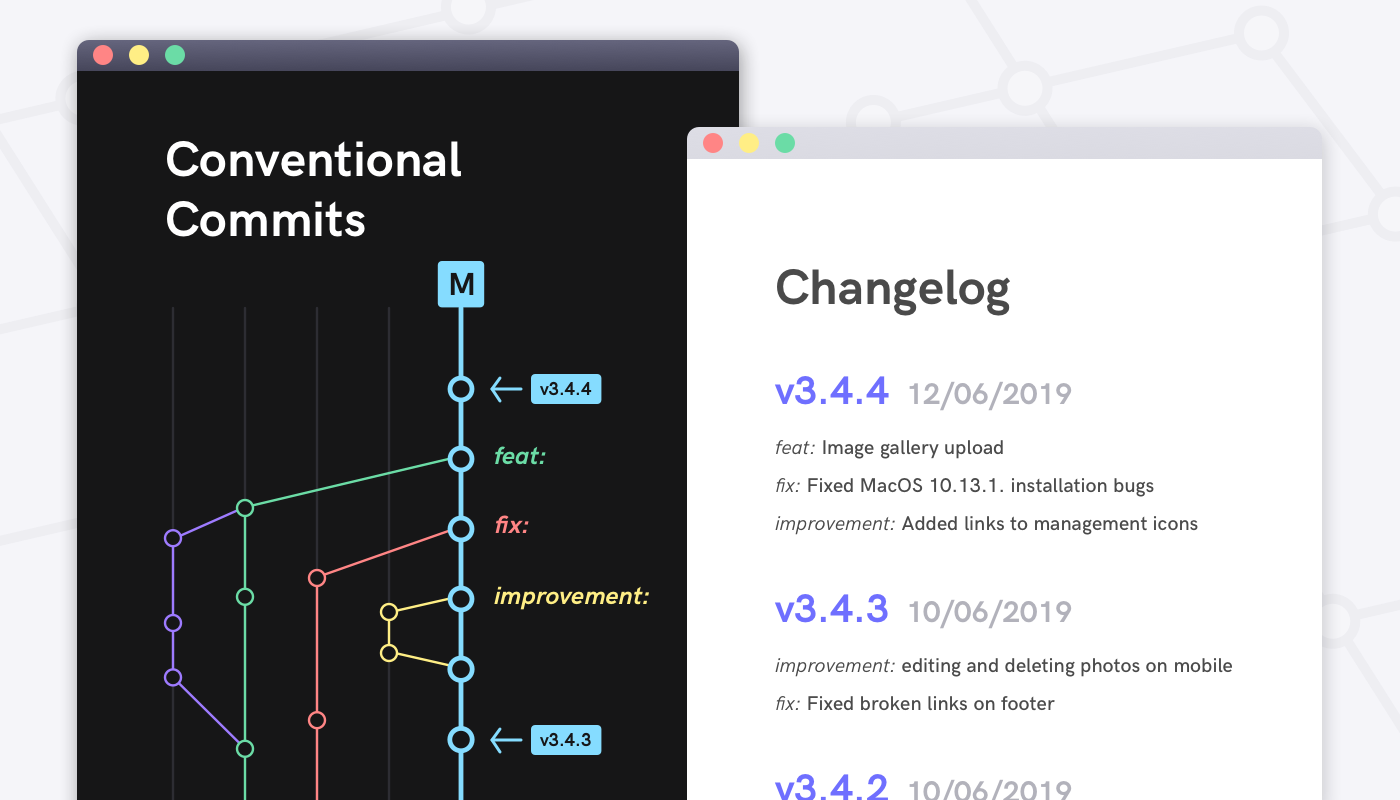

Benefits of using Conventional Commits:

- Automatically generating CHANGELOGs

- Automatically determining semantic version bumps

- Communicating the nature of changes to teammates and stakeholders

- Triggering build and publish processes

- Making it easier for people to contribute to your projects

Branch Naming

Before making changes to the code base, we all create a branch. Managing these branches can become difficult in some cases. To prevent this, effectively naming and organizing branches can increase the efficiency of the development process.

Regular Branches

Regular branches in Git are long-lived branches:

- Master (master/main) Branch: The default production branch

- Development (dev) Branch: Main development branch for integrating features

- QA (QA/test) Branch: Branch containing code ready for QA testing

Style

- Lowercase and hyphens: Use lowercase letters and hyphens to separate words. Example:

feature/new-login - Alphanumeric characters only: Only use alphanumeric characters (a-z, 0–9) and hyphens

- Avoid consecutive hyphens:

feature--new-loginis confusing - Don't end with hyphen:

feature-new-login-is incorrect - Be descriptive: The naming should reflect the work done in the branch

Branch Prefixes

- feature/: New features. Example:

feature/login-system - bugfix/: Bug fixes. Example:

bugfix/header-styling - hotfix/: Critical production fixes. Example:

hotfix/critical-security-issue - release/: Release preparation. Example:

release/v1.0.1 - docs/: Documentation changes. Example:

docs/api-endpoints - experimental/: Experimental features. Example:

experimental/new-algorithm - wip/: Work in progress. Example:

wip/refactor-auth-system

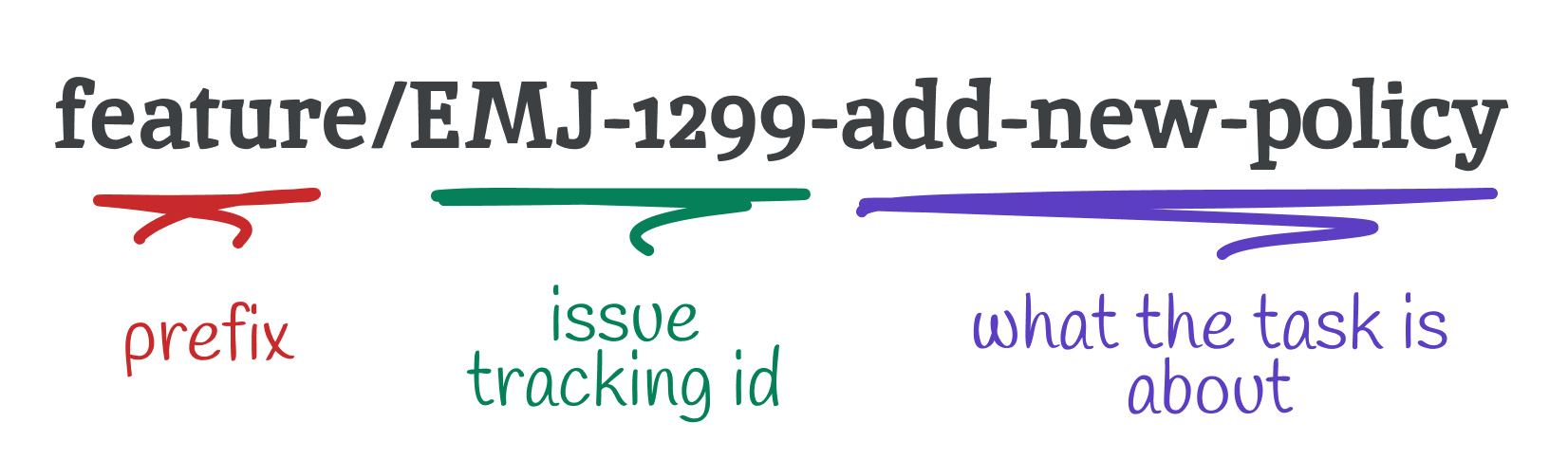

Including ticket numbers from project management tools is common:

bugfix/EMJ-1789-fix-header-stylingfeature/US-1288-new-login-systemfeature/T-1289-new-login-system

Whether to apply these standards or postpone them is up to you. However, we shouldn't forget LeBlanc's law that Robert C. Martin refers to in Clean Code: "Later equals never." 🙂

Sources: